|

Report

on Sawin's

and Williams Ponds

By Brian J. Le Blanc, November

5, 2003

Before

I begin, I wanted to

take this opportunity to thank those who spoke to me about Sawin's Pond

and

shared their insights and information, including Bruce Roberts, Susan

Falkoff,

Daphne Collins, Joe Di Vico, Diana Proctor, Angie Kounelis, and John

Airasian. I

also wanted to thank the Watertown Main Public Library, and the

Conservation

Commission for granting me both access to their files and allowing me

to speak

here tonight.

I came here tonight because I want to see Sawin's

and

Williams Ponds

cleaned up, but before we can clean them, we must understand how it

happened.

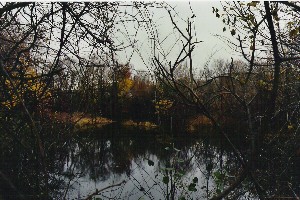

Sawin's

and

Williams Ponds are

parts of a brook that runs through East Watertown. In this 1853 map

(Fig. 1),

you can see the body of water in closest to its most natural form. It

starts as

a forked brook to the south of Mt. Auburn St. and west of the Old

Burying Ground

near present- day Porter St. From there, it flowed easterly until it

crossed

under the newly built railroad tracks, down underneath Arlington St,

and finally

into the Charles River.

|

|

|

|

Figure

1: Plan

of Watertown 1853

Image

consisting of four quadaents, click for larger image.

|

|

In the late 1800s, three

people decided to seek their

fortunes by

developing land around the brook, one man with an eye to utilize the

natural

beauty of the area, and two brothers who wanted to take advantage of

the

confluence of a railroad line and a water supply.

George

W. Sawin was, in the late 1870s, the proprietor of

the Union

Market Hotel, which was on Walnut St. near the Union Market train

station. It

was a successful hotel, but Sawin had bigger plans. On November1st,

1878, he

purchased a tract of land between Arlington and Coolidge St, which

contained a

small glen that the brook ran through, “ for the purpose of flowing

said

meadow and for the purpose of a fish pond and for cutting ice upon the

same…” ([Book 1502, Page 558], from Title to Sawin's and Williams

Ponds

3/22/1973). Sawin also purchased a pond that had been made between

1851 and

1880 from Josiah Williams on July 31, 1880.

Sawin constructed a dam at Coolidge St and flooded

the

glen, creating a

pond several times larger than the one he had purchased from Williams.

It was

the finishing touch of the resort that he had built to overlook the

pond. He

also constructed a new street, Glen Rd, which provided access from

Coolidge St.

The Glen Hotel held its grand opening on Thursday evening, September 1st,

1881.

An October 5, 1881, article from the Watertown Enterprise

called “ A

Model Suburban Hotel, “ extols the virtues of Sawin’s new resort:

“For

healthfulness and

grandeur of scenery at all

seasons of the year, the location of this house cannot be excelled. On

the

premises is a beautiful pond, where the guests can enjoy a boat sail in

the

summer or skating in the winter. While on both sides of the pond are

beautiful

groves, well provided with swings, croquet grounds, bandstand, and all

the

etceteras of pleasure and pastime. “

In June 1882, a sting operation was conducted aimed at the

liquor dealers

of Watertown. State Officers employed three underage youths from Boston

as “ spotters “ to see who

would sell them alcohol. In all,

twenty

violations were handed out to the liquor dealers. The Glen Hotel was

one of the

alleged violators. According to the account of the “Liquor Trials”

published

in the June 28, 1882 edition of the Enterprise, “ The case of Sawin was

discharged because (“ spotter “ Thomas) Doorley testified that he

bought the

liquor of a barkeeper, Sawin being absent. The ruling of the Judge was

that a

dealer is not liable for the action of an agent, which may be contrary

to his

expressed of implied wishes. “

George W. Sawin may have won his court battle, but

lost a

great deal of

face in the eyes of Watertown society. His reputation, and that of his

“ model

suburban hotel, “ was besmirched, and it soon became known in town

legend as a

house of ill repute. He renamed the hotel several times, but the

business was

never as it was for that short wonderful period. In 1883, he sold part

of the

land to Harvey, including use of the pond, but retained all rights to

cut ice.

By the early 1890s, it was no longer listed as a hotel in the Watertown

directories, only that Sawin lived at 45 Arlington St.

Frederic

C. and Arthur N. Hood, on the other hand, were brothers who had spent

several

years learning the rubber business by working in the factories. By

1896, the

Hood brothers, now full of ideas, were ready to start their own

business. They

bought land bordered on the north by Nichols Ave and on the south by

the

railroad. The brook ran diagonally through the site, and was to provide

the

cooling water and power necessary to running a rubber factory.

The Hood Rubber Company opened in November, 1896.

Their

small operation

soon grew rapidly and they purchased the land on the other side of the

tracks

down to Arsenal St. Sometime between 1901 and 1905, Hood Rubber Company

bought

what were now called Williams Pond and Sawin's Pond from George W.

Sawin.

In all, the Hood Rubber Company at its height in the

early

1920s,

controlled over 80 acres of land, employed around 10, 000 people, and

produced

all manner of rubber products, including tires, boots and PF Flyers,

one of the

earliest sneakers. In 1929, the Hood Rubber Company was bought out by

the B.

F. Goodrich Corporation and renamed the B. F. Goodrich Footwear

Company, but

most people in Watertown continued to refer to it by its former name.

|

|

|

|

Figure

2: Map

of East Watertown

1925

Image

consisting of four quadrants, click for larger image.

|

|

The brook was harnessed for use within this massive

factory complex

mainly as coolant in the rubber treatment process. As the Hood plant

expanded,

the brook was culverted, built over, and incorporated into the storm

sewer

system of Watertown. For a time, the area that is now the front parking

lot of

the Watertown Mall was flooded and turned into a large industrial

lagoon called

Hoods Pond in 1907. Hoods Pond was shown on maps (see Figures 2 and 3)

until

around 1935

when it was filled in so the plant could expand further. The water that

the

plant needed was now pumped offsite from Sawin's and Williams Ponds and

returned

there through a series of culverts. The water, which had been subject

to

industrial processes, emptied out of Sawin's Pond and into the remnants

of the

brook which flowed alongside Arsenal St. to the Charles River.

|

|

Figure

3: Map

of Watertown 1935

Image

consisting of two quadrants, click for larger image.

|

|

In the

1940s, the pond that Sawin had left behind was a

recreational

space for the people of the neighborhood. It was still fishable and

swimmable. Joe Di Vico, who moved to the area

with his family in 1932

from Italy

told me that the kids referred to the pond as the “ Sois, “ or the “

Soines. “ The area behind the ponds was still partially open land that

the

Italian immigrants farmed on land owned by the Town. The area where the

UPS

building is now was a wooded area that overlooked the pond where Army

soldiers

camped during World War II.

Joe Di Vico told me that by the 1950s, Sawin's Pond was no

longer

swimmable, and the Town told the immigrants that they could no longer

farm

there. The area had been zoned for industrial use. The dumps grew

larger, while

on the area along Glen Rd, which was now a private way, industrial

businesses

grew up on the former farmland. By the 1960s, Sawin's and Williams

Ponds were in

bad shape. The ponds had been encroached on all sides by industrial

businesses.

In 1965, the Hatch Act went into effect in Massachusetts, which forbade

the

alteration of any natural or man- made body of water without

authorization from

state and local government.

In the summer of 1966, the B. F. Goodrich Footwear Company

now had to

apply to the Massachusetts Department of Natural Resources, as well as

the

Watertown Planning Board, Board of Health, and Conservation Commission

to do

maintenance work at Sawin's Pond. They proposed six items, including

dredging

the pond. They wanted to continue to dump “ rubbish “ in the landfill

method

by building two dikes, decreasing the pond’s water capacity by filling

it with

trash. They also laid out a longer- term strategy of culverting

Williams Pond

for landfill. According to R. T. Wise, Superintendent of Engineering

and

Maintenance at B. F. Goodrich Footwear Company, “ (t)hese changes are

needed

so that essential industrial water supply and rubbish disposal can

continue in

the Sawin's Pond area. “ ( R. T. Wise letter to the Commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Natural Resources

7/ 6/

66)

The Planning Board, Board of Health, and the Conservation

Commission all

agreed to part of the work scope. A June 29, 1966 letter from R. B.

Chase of the

Watertown Conservation Commission specifically approves two of the six

requests

of B. F. Goodrich: 1) to dredge Sawin's Pond and 2) to build a dike

along the

East side “and use the area between the fence and dike for landfill

rubbish

disposal.“

From

1966- 68, while B. F.

Goodrich was considering if staying in Watertown was part of their long

term

corporate strategy, they dumped a great deal of “ rubbish “ consisting

of

rubber scraps, some contaminated with solvents and plasticizers, with

approval

from town and state officials.

In December 1969, the B. F.

Goodrich Footwear Company closed

and moved operations to another plant in the Carolinas. It was said

that they

started to lose money in 1966. My great uncle, Patrick Callaghan, lost

his job

and his pension, as did 1,300 other workers.

Within the space of 4 years, over 130 acres of nearly

contiguous land,

formerly occupied by a U. S. Army munitions factory where they did

uranium and

nuclear testing, a rubber plant, two town dumps, and two polluted ponds

were

abandoned. A citizens panel, the Watertown Redevelopment Authority, was

formed

to purchase the Arsenal land and form a strategy of how to reintegrate

all of

this land back into East Watertown. Initially, ideas were put forth to

build a

“Mini- City” that incorporated both sides of Arsenal St. The B. F.

Goodrich

property, which included the ponds, was still owned by the company, and

they

were not all that interested in selling such lucrative property back to

the

town.

After B. F. Goodrich ceased operations, several local

businesses that

abutted Sawin's Pond installed illegal sewer hookups to drain into the

pond,

knocked down the fences to park trucks, and threw in all sorts of

garbage on top

of the unkempt piles of rubber waste. One business went so far as to

knock down

the fence to make a concrete ramp into Sawin's Pond so they could throw

broken

concrete burial vaults.

By 1973, the Berkeley and Clarendon Streets neighborhood,

which was next

to the ponds as well, had enough and lobbied the East Watertown

Betterment

Association to ask the Conservation Commission to fix this situation.

B. F.

Goodrich, who was trying to sell the property, removed excess rubbish,

brought

in fill to grade the banks, seeded it, and repaired the fence. The work

was

completed mere days before the sale of the property which was sold to

Wasserman

Development Corporation in the summer of 1973.

Max

Wasserman was sympathetic

to how Goodrich had mistreated both Watertown and the ponds. In March

1974, he

offered to sell Sawin's Pond to the town for $1.00 if they would allow

him to

culvert Williams Pond. Churchill indicated that the Town wanted to

preserve them

both. Wasserman resold the entire property to Campanelli Brothers and

their

partners, Corporate Property Investors, in December 1974.

From 1975- 83, Sawin's and Williams Ponds, fenced in and

overgrowth obscuring them from view, had a brief respite to begin

repairing

themselves.

The respite ended on January 29- 30, 1983, when 1000

gallons of PCBs from

a broken electric transformer spilled into a catch basin located at the

Boston

Edison building, which was built on the site of the original Hood

factory. The

PCBs went through the culverted brook and into the ponds. The

Environmental

Protection Agency and the Massachusetts Department of Environmental

Quality

Engineering were alerted to the spill. Eric Campanelli decided now was

the time

to finally offer to give the ponds to Watertown. The Town Council,

fearful of

having not only to pay for the ponds but have to clean them as well,

voted down

the proposal.

In April

1984, two brothers, Maximos Hatziiliades and Savvas

Iliades, owners of Western Roofing Company, purchased the property from

the

Campanellis. They proposed to build a parking lot in between the pond

next to

their commercial property on Arlington St. The Conservation Commission

was

determined to protect Sawin's and Williams Ponds from further

encroachment

because they are wetlands that are part of the natural drainage system

of East

Watertown.

The

Commission rejected the

Hatziiliades’ parking lot proposal, saying that they could not build

within

the 100’ buffer zone mandated around all wetland areas by the Wetlands

Protection Act. The Hatziiliades’ appealed and the Massachusetts DEQE

overruled the Commission’ s decision. This was merely the first

skirmish in a

prolonged litigation battle over the fate of Sawin's and Williams

Ponds.

Therein

lies the story of Sawin's

and Williams Ponds up to the present: they were artificially created

out of a

natural brook, polluted by industry, and left for others to clean up.

Despite

the fact that the Hatziiliades’ had not polluted their property but had

merely

purchased it in that condition, they are, under environmental law, are

responsible for cleaning it up.

In

March 1985, as a result of

the 1983 PCB spill, Sawin's and Williams Ponds were placed on CIRCLIS,

an EPA

database of potential controlled hazardous waste sites. The

Hatzilliades’

retained the services of Certified Engineering and Testing Co. to

determine the

causes and extent of the pollution. On April 29, 1985, Maximos

Hatziiliades was

served with a cease and desist order from the DEQE for “ intentionally

breaking the dike “ at Sawin's Pond, which lowered the water levels and

compromised the wetland.

It is this move that truly turned the Conservation

Commission’ s

attention to Maximos Hatzilliades. From this point on, the parking lot

proposal

and anything they wanted to do around the ponds was heavily

scrutinized. In

1986, the Commission denied the parking lot proposal again and

initially denied

a request to bore testing holes for soil and water samples, even though

they

were being conducted with the approval of the DEQE.

In

1987, the Commission passed

the Watertown Wetlands Ordinance, which prohibited building within 150’

of a

wetland. The Commission also handed out numerous citations to

Hatziiliades for

violations such as dumping into the ponds, leaving the gates open, and

parking

trucks next to them.

By

1989, Certified Testing and

Engineering had completed their initial assessment of Sawin's and

Williams Ponds

by looking at the site history and conducting water and soil samples.

They

discovered that the pond was created as a source of ice, and that Hood/

B.F.

Goodrich had polluted it over a number of years. They concluded that

although

the rubber scraps may be contaminating the groundwater, it was better

to leave

them buried, and that the source of much of the water pollution was the

runoff

from the town drainage system. They also recommended that the Town help

by

installing particle separators in

the storm drains.

In

1990, Hatziiliades

submitted a waiver application to the DEQE that would allow him, as the

owner of

the site, to remediate it without oversight, and was approved. This

means that

the DEQE and the EPA saw that the ponds were polluted but they did not

pose

enough of a threat to public safety to have to clean them

immediately.

The

Conservation Commission

did, however get the DEQE to make the ponds a Public Involvement Plan

site.

Hatziiliades had to prepare a report about the condition of the ponds

and their

plans for remediation, and file a copy of it at the Watertown Public

Library. In

the Sawin's and Williams Ponds Disposal Plan dated November 16,

1990, it

states that “ a portion of the site is proposed for development of

commercial

buildings and a park, “ and that “Maximos

Hatziiliades, property owner is prepared to pay the estimated $45,000

cost

incurred from the proposed remediation action.“ The Commission issued a

rebuttal disputing most of Certified’ s findings.

In1990 Hatziiliades applied for a third time to build the

parking lot. He

was denied once more, appealed, and received a hearing in front of

Administrative Judge Francis X. Nee. In June 1994, the Department of

Environmental Protection (formerly the Dept. of Environmental Quality

Engineering) found in favor of Hatzilliades’ proposal to build a

parking lot.

The Commission argued that Maximos Hatziiliades’ past actions showed

that he

“ could not be trusted, “ but Nee ruled that they had “not established

a

nexus between the applicant’s record and the issue, “ and concluded

that “

the Applicant’s record is not relevant to the issue.“

In

the fall of 1997,

Hatziiliades’ decision to not pay his property taxes in protest of his

treatment came back to haunt him when Watertown seized Sawin's and

Williams

Ponds as payment. Hatziiliades appealed this decision to the

Massachusetts Land

Court, but the Commission was hoping to have the Town get the ponds in

order to

settle his tax debt.

In

October 1998, the DEP

overruled the Commission’s decision in favor of Hatziiliades. After the

decision, Hatziiliades paid $21, 000 in back taxes, and the Land Court

ultimately gave ownership over his property back to him.

Hatziiliades

no longer needed

a parking lot for his business, but he found a new partner in the

neighborhood.

A popular gym called Super Fitness had opened next to Williams Pond but

it had

no parking lot, creating a traffic mess on Arlington St. Super Fitness

agreed to

lease the parking lot, and the Town finally allowed work to begin on

the parking

lot on February 8, 2000. Eighteen years after it was proposed, the

parking lot

was built and was completed in the fall of 2002.

The completion of the parking lot meant something quite

different to both

parties. For Maximos Hatziiliades, it represented a long- fought

victory. For

the Conservation Commission and their supporters, it was a disgraceful

end to a

long struggle to preserve encroachment upon the last remaining wetlands

in East

Watertown. Although I do not have a first- hand perspective on these

events, and

am merely writing the first historical account of it, I believe that

the

Commission fought so hard against Maximos Hatziiliades because many of

them

remember Sawin's Pond in all its glory. They had watched while it was

almost

destroyed and left for us to clean up. The Watertown Conservation

Commission

made sure that both Sawin's and Williams Ponds were saved from

destruction and

polluted as little as possible. They were enforcing laws that are

designed to

protect the land over the intentions of the landowner.

In the end, both sides got so caught up in the struggle

over the building

of a parking lot that they seem to have forgotten that Sawin's and

Williams

Ponds are still not clean, and have been hidden from public view for so

long

that most people in Watertown are unaware of their existence.

Several

people I have spoken

to who support the Conservation Commission's efforts think that the

only

solution is to have Watertown somehow seize the land, and even that was

tried

and did not work. Maximos Hatziiliades has asserted in the courts his

right to

develop within reason on his own property. This stalemate could

continue

indefinitely, but is it still possible for both groups to work together

to

improve the property? Would the Conservation Commission be willing to

allow

Maximos Hatziiliades to redevelop his property into something that

would

overlook and incorporate a remediated Sawin's Pond? We need to come to

a

reasonable compromise.

It

is the twenty- first

century, and East Watertown is a very different place. Where there were

once

factories, there are malls and office parks, and very little

undeveloped land.

The railroad tracks, except for a small spur from Fresh Pond down to

Grove St,

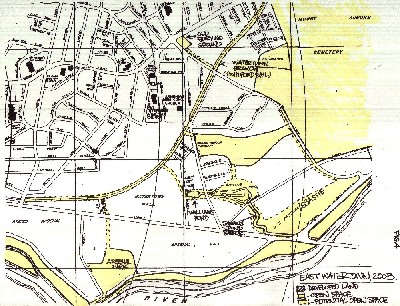

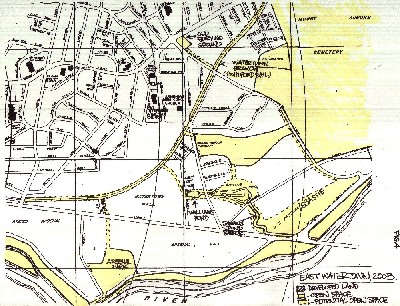

lie abandoned. I began to see a path that connected the potential open

space in

East Watertown. If you look at the map of my open space proposal the

walkway

starts at School St and follows the railroad tracks, going behind the

Watertown

Mall to Elm St. and Williams Pond, then to Sawin's Pond, alongside

Sawin's Pond

Brook, down along the GSA Site and up to Grove St to Fillippello

Park.

This

is the last part of the

redevelopment of East Watertown- the remaining land has to be preserved

as open

space. If we could just remediate Sawin's and Williams Ponds, it would

be the

start of a much larger project.

A

plan needs to be developed

that results in the clean up of Sawin's and Williams Ponds. Doing this

can be

the cornerstone of an open space master plan that unites the ponds,

brook, and

marsh into a whole once more, as a symbol of the final phase of the

redevelopment that began over 35 years ago.

By

doing so we could create a

walkway not unlike the Emerald Necklace. Think of the aesthetic and

economic

benefits that such a walkway could bring to East Watertown. It may take

a long

time, but if anything is going to happen we need to have a catalyst.

Perhaps the

Conservation Commission could take the initiative and attempt to make

peace with

Maximos Hatziiliades in order to begin the cleaning of Sawin's and

Williams

Ponds.

Thank

you.

Figure 4: Open Space

Plan

click on the above image for the full

size

version.

|

Maps courtesy of the

Watertown Public Library, Historical Map Collection.

Questions, comments? Contact Brian at brianleblanc AT athenaverse.com

|